by Laurie Pickard | Sep 20, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

What is the purpose of an MBA? I’m sorry to get all philosophical on you, but someone asked me the other day, and while I was able to rattle off a list of skills that I have learned since embarking on this journey (reading a balance sheet, calculating NPV, analyzing recurrent processes and finding inefficiencies,etc.), I wasn’t able to come up with an overarching statement of purpose regarding what an MBA is supposed to be or do.

The conversation left me thinking about whether an MBA is supposed to be management training, or whether it is more technical training. In trying to answer this question, I went back to an excellent article by Brooke Allen called ‘How to talk yourself out of getting an MBA.’ The article refers to a book called Managers, Not MBAs, which is also a great read. Both of these works set up the MBA as a management degree, then proceed to tear it down. As Henry Mintzberg, the author of Managers, Not MBAs says,

“It is time to recognize MBAs for what they are - or else close them down. They are specialized training in the functions of business, not general educating in the practice of managing. Using the classroom to help develop people already practicing management is a fine idea, but pretending to create managers out of people who have never managed is a sham.”

I suppose I agree with Mintzberg, and with Allen, that you can’t expect to learn how to be a manager from an MBA program. From what I’ve seen so far, getting an MBA is unlikely to make someone a good manager. But maybe that’s not a problem. I’m finding plenty of value in learning the “functions of business” and in learning to perform the types of analysis that are particular to business. In fact, maybe a better title for the degree than Master of Business Administration would be Master of Business Analysis.

But what if what you really want to learn is how to be a manager? If you can’t learn management in a business administration program - and frankly I agree with the two previously mentioned authors that if this is what you want to learn, then business school is probably not the place for you - where do you learn that skill set? I have four suggestions on where to start.

Managing yourself

I recently read a book called Business Without the Bulls%*t, in which the author starts the book by claiming that everyone is essentially a freelancer. What he means by this is that a good worker needs to manage him or herself - understand what is expected of you at work, and get things done well and on time without much oversight. The first place to learn management, then, is by managing oneself. You can find lots of great personal productivity tips on YouTube. Degreed.com also has a great Productivity Learning Pathway with some very useful resources.

Managing your boss

The second place to learn management is by managing your boss, also known as “managing up.” This is an extremely important skill in most if not all workplaces. Business with the Bulls*%t has some great, specific suggestions on how to do this. The key is to take your boss’s perspective of the work that needs to be done, and then act so as to make it happen. It means knowing the details of a particular task even better than your boss does, so that you can anticipate what kind of time and attention will be needed from your immediate supervisor and also his or her supervisors. It means seeing how your work fits into the bigger picture, identifying gaps, and filling them in.

Managing the work

One of the best ways to get management experience is to manage a process with a specific desired outcome. Even if no one reports to you on their day-to-day work, you can still get valuable management experience by taking the lead of an ad-hoc team that is expected to produce a certain product or result.

Management = harnessing motivation

I do believe that the best place to learn management is in the classroom - just not as a student. I spent two years as a middle school teacher, and looking back on that experience, I’ve come to understand it as an excellent crash course in management. In fact, teachers even use the term “classroom management” to describe techniques for keeping students on task. The more motivated and self-disciplined people are, the less they need to be managed by someone else. Children are not known for their self-discipline, which is why management in the classroom can be a trial by fire. But a good teacher can always tell you what the students are supposed to be doing - and tries to minimize the time that students are passively absorbing information. Likewise, teachers who make classroom management look effortless are those who are able to understand and harness the innate motivations of their students.

Shouldn’t a good manager be able to do the same for their employees? If you give people work that uses their talents, engages their interests, and then allow them to do the work in the way they see fit, they will require very little management from above. And a manager who understands the value of his or her employees’ time will likely ask them to spend less time in meetings where their only expected role is to absorb information.

The purpose of an MBA

I’d be curious to hear from readers - what do you think is the purpose of an MBA? Are there management skills that are no easier learned as a student in a brick-and-mortar classroom than as an online student? If so, what do you see as the best way to pick up these skills?

by Laurie Pickard | Sep 7, 2014 | MOOC MBA Design, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

Most of the discussion about MOOCs and their advantages has focused on price (cheap or free) and teaching methodology (flipped classroom, lectures that can be viewed again and again). But as I am discovering, a MOOC-based learning program has two other much less-discussed advantages, especially for working professionals – customizability and immediacy.

As you know if you’ve been reading this blog, my goal is to mimic a traditional MBA education using MOOCs and other free resources. I’ve used the curricula of top MBA programs like Wharton, Harvard, and Stanford to come up with my list of courses and topics. (If this is something you’re interested in, you can find more info on my Curriculum page, or on the MBA Learning Pathway on SlideRule, which I helped to create). But recently I strayed from the traditional MBA curriculum to take a course on Social Psychology, and I’m very glad I did.

Somehow I managed not to take any psychology courses in college, despite having an interest in the subject and the fact that my roommates in both undergrad and graduate school were psych majors. It seemed like a hole in my education, and I thought a bit of education on the subject as might serve me while navigating interpersonal relationships in the world of work. Even though it isn’t a topic that is typically covered in business school, taking this course has convinced me that it should be. Social Psychology was packed with pearls of wisdom about perception, biases, and decision-making – all relevant to work in any office. One of the most interesting units was on group behavior, covering such phenomena as the Abilene Paradox, in which fears of non-conformity cause a group to arrive at a decision that no one actually thinks is a good idea. Being aware of this tendency and taking simple steps to counter it can actually prevent a group from going down an unproductive path.

Because I am setting my own curriculum, and because the entire universe of MOOCs is open to me, I am able to tailor my curriculum to very personal specifications and to include courses like psychology that aren’t covered in most MBA programs. I see this as being a great advantage of my chosen method of study.

My next set of courses also includes personally relevant offerings that aren’t always in the B-school lineup. One is Supply Chain and Logistics Fundamentals, the first in MITx’s long-awaited supply chain and logistics management series. The other is a course on evaluation of social programs from MITs Poverty Action Lab, which pioneered the use of randomized control trials for international development interventions. The latter, by the way, will be my first course on data analysis.

As I did with Social Psychology, I’m straying outside of a narrowly-defined business curriculum to take Evaluating Social Programs. While my overarching goal is to acquire a particular set of business skills, I am interested in any course with the potential to make me a better professional. As a designer of social programs and a consumer of program evaluations, my expectation is to be able to put what I learn in this course into practice in my current job. Which brings me to the second less-discussed advantage of a MOOC education – immediacy.

While I suppose any study-while-working program has this advantage, being able to use new knowledge and skills immediately in a real-world setting is enormously valuable for cementing what you’ve learned. MOOCs also offer another kind of immediacy – there is almost no cost to changing your mind. If you discover that a course is not what you were expecting, or doesn’t meet your needs, you can choose to study something different without waiting an entire semester and without losing any money. The only sunk cost is the time you’ve already put in to the course. In both of these ways, the feedback cycle on MOOCs is short. If, like me, you’re mapping out a series of MOOCs to achieve a larger educational goal, you can easily course correct if you need more or less of a certain topic, or if you discover gaps in your learning program.

I’m not sure how many “non-MBA” courses I’ll end up taking over the course of my studies, just as I’m not sure how many courses in finance I’ll include. It depends on the opportunities that arise and the learning needs I discover along the way.

by Laurie Pickard | Aug 22, 2014 | Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

I’ve posted a couple of articles recently on the No-Pay MBA Facebook page suggesting that perhaps the low completion rates in MOOCs are not evidence that they are a failed experiment. As an Atlantic article recently put it,

“Out of all the students who enroll in a MOOC, only about 5 percent complete the course and receive a certificate of accomplishment. This statistic is often cited as evidence that MOOCs are fatally flawed and offer little educational value to most students. Yet more than 80 percent of students who fill out a post-course survey say they met their primary objective. How do we reconcile these two facts?”

I’d like to add my voice to the chorus of people who are saying that maybe it’s completely understandable that only a slim minority of MOOC registrants make it all the way to the finish line.

The way I see it, there are two ways MOOCs can be valuable. A MOOC can either build your knowledge about a particular subject, or it can build your skills to apply knowledge in a particular way. I’ve written about my strong preference for skills building courses, but I see the value in both types of learning.

Ways of knowing

One of the things I’ve found most valuable about studying business via MOOC is the process of discovering – and putting firmer boundaries around – what I don’t know. It’s like the elephant parable, which you have probably heard if you have ever done any type of leadership or team-building retreat.

Basically, a bunch of people in a dark room are all standing around an elephant, touching it and describing what they feel (“It’s soft!” – the nose; “It’s rough and hairy!” – the skin; “It’s smooth and hard!” – the tusks) and trying to figure out what it is. Eventually they figure out that it is an elephant, but only with everyone’s input – hence the team-building connection. (Just as an aside, having been charged by an elephant, I can tell you that it’s probably not a great idea to put one in a dark room and let a bunch of people feel it up. )

Photo credit: Ethan Handel

Photo credit: Ethan Handel

For me, putting together an MBA curriculum is like the elephant parable. Each course provides information about what an MBA really is. The elephant begins to take shape. Even as I realize how many things I still don’t know about it, I start to recognize it for what it is. I refine my understanding of it.

If you ever work with me you will learn that I think in matrices. It’s a good thing I was born into the information age because without Excel I basically wouldn’t have a way of organizing my thoughts.

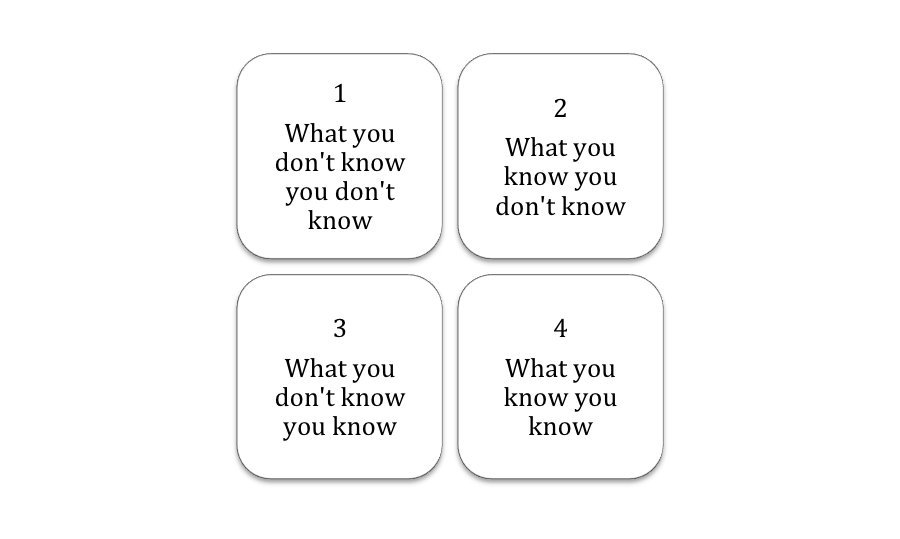

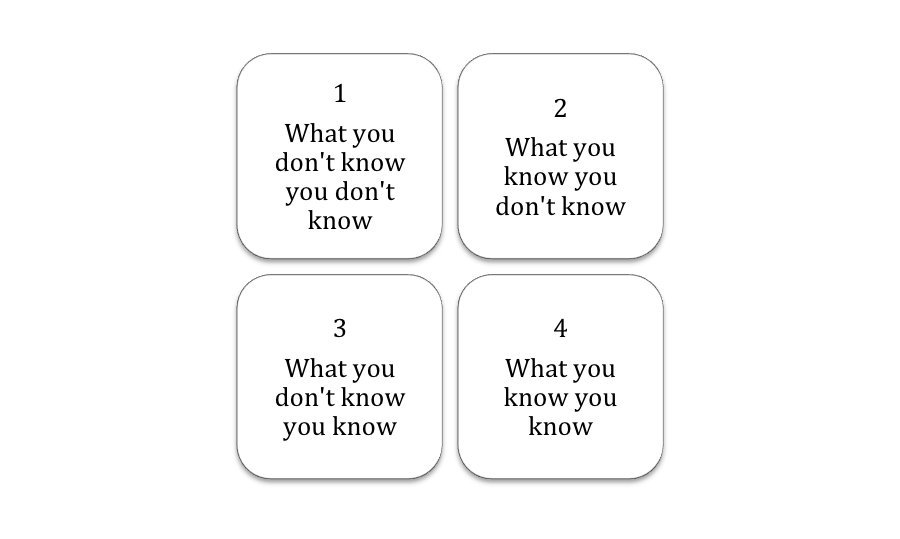

Here’s one:

MOOCs are really good for moving from Box 1 to Box 2 – that’s knowledge building. For example, prior to taking a course on corporate finance, I would have been hard-pressed to even identify the types of situations in which corporate finance is used. Now, while I am not an expert in the subject – you wouldn’t hire me to value your company prior to a sale – I am conversant in financial terminology. That is valuable in and of itself, apart from any skills I may have learned.

MOOCs are really good for moving from Box 1 to Box 2 – that’s knowledge building. For example, prior to taking a course on corporate finance, I would have been hard-pressed to even identify the types of situations in which corporate finance is used. Now, while I am not an expert in the subject – you wouldn’t hire me to value your company prior to a sale – I am conversant in financial terminology. That is valuable in and of itself, apart from any skills I may have learned.

MOOCs can also move you from Box 2 to Box 4, though it is more difficult. Moving from Box 2 to Box 4 is what happened when, after learning that corporate finance is used to make investment decisions, I learned how to calculate the net present value of an investment.

MOOCs can even generate movement from Box 3 to Box 4. You might say Box 3 doesn’t exist – how can you not know something you know? Well, sometimes you realize that a concept you understand very well is called by a different name – like the fact that my employer, USAID, uses the term “cost-benefit analysis” for what I know as “net present value.” Sometimes you find that something you intuitively understand actually has a formal definition and is associated with particular methods. For example, my course on business strategy validated my matrix method, which I had no idea was part of business strategy until I took that course.

In fact, this type of movement – discovering what I didn’t know I knew – has been crucial in providing me with the confidence to present myself as someone who can offer most – if not all – of what an MBA-grad can offer. With all the hype surrounding MBAs, the de-mystification of the degree is really useful. By the way, if you are someone who hires MBAs or who competes with MBAs in the job market I highly recommend you at least audit some business MOOCs as a way of understanding what you’re dealing with.

It’s all about incentives

For those who are using MOOCs to build knowledge, watching a few videos may be enough. As the quote at the beginning of this post suggests, most students come away from the MOOC experience satisfied.

For those of us who are interested in building skills, completing the assignments may be more important. But even for us, what is the incentive to complete every course requirement and earn a Statement of Accomplishment?

I’ve set up this whole website basically as an incentive to myself to complete my courses. Because finishing courses is hard, and you need a good reason to do it. MOOC certificates don’t have any proven value – at least not yet, and certainly not in comparison to a degree. If finishing a course – meaning that you’ve earned a certificate – won’t provide any marginal value over watching some videos and possibly completing an assignment or two, then it’s really not surprising that most people don’t do it.

Question: Without this blog, would I be wiling to stick it out for every course?

Answer: Probably not.

Capturing value

Now for the big question:

How will anyone capture value from all the knowledge and skills that MOOCs are building?

MOOCs are most certainly creating value. All that learning is important. And someone will figure out how to monetize it – probably soon.

Maybe one day I’ll even be able to trade my set of certificates in for a degree, though I doubt it. A more likely scenario is that I will be able to convince an employer that my MOOC education has equipped me with skills and knowledge that have increased my productivity – and will pay me accordingly.

by Laurie Pickard | Aug 15, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs

I’ve always had a distaste for the idea of marketing. I saw marketing as a fluffier part of business – as compared to subjects like accounting and finance – and I was uncomfortable with the idea that corporations actively work to shape our desires. I might not have taken a marketing course at all, if it weren’t for the fact that I’m using MOOCs to mimic a degree-bearing MBA program course-for-course, and most if not all MBA programs include at least one course on marketing.

Introduction to Marketing, a MOOC from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, quickly disabused me of my mistaken notions about marketing. In fact, by the end of the course I was convinced that marketing is a central component of business strategy – perhaps the central component. The course is taught by three professors – Barbara Kahn, Peter Fader, and David Bell. Each prof teaches one unit – Branding, Customer Centricity, and Go-to-Market Strategies, respectively. Introduction to Marketing is part of the Wharton foundational series – along with Introduction to Accounting, Introduction to Operations Management, and Introduction to Corporate Finance. I’m still counting my lucky stars that one of the top business schools in the country started giving away free online versions of its core courses just as I started putting together my free version of an MBA.

Without further ado, let’s go through my three-part rubric for evaluating online courses.

Am I checking my email during the video lectures?

No issues in this department. The lectures were interesting and engaging. Each professor’s deep and obvious passion for his/her subject matter helped to keep my interest level high. Having three distinct perspectives also contributed to my experience. I appreciated that the videos were clean – often, the professor would speak against a white background, with nothing else on the screen. Rather than relying heavily on slides, key words would appear on the screen in the white space surrounding the professor. The lack of visual distraction helped me stay focused on the content.

As previously mentioned, this course changed my view of marketing. Marketing is not just about advertising – it’s about MARKETS. Who are your customers? Where do you find them? What value do you propose to create for them, and how do you let them know about it? How do you address the fact that your customers are individuals, with unique desires and preferences? Professors Kahn, Fader, and Bell covered these and other topics in a conversational but highly informative manner.

Do the assignments require serious thinking?

Unfortunately, the assignments in this course offered little of substance. There were weekly readings and a quiz after each of the three units. The quizzes were good, as were the readings, but I would have appreciated at least one assignment requiring me to apply some of the concepts I had learned.

Is there a practical application for what I’ve learned?

The information covered in this course is extremely practical, as it informs businesses’ orientation towards their customers. The professors did a good job of using real businesses to illustrate their points. Again, the one thing I felt this course was missing was a “how-to” element. While I could clearly see that marketing concepts have practical applications, I would have liked more instruction – and more practice – on how to apply these concepts myself.

The bottom line

Overall, I have found the Wharton courses to be very high quality. Introduction to Marketing is no exception. This course is well worth the 1-2 hours per week it takes to watch the videos and read the assigned readings. However, you will have to look elsewhere to find ways to practice applying marketing concepts.

This post originally appeared on the website Poets and Quants.

by Laurie Pickard | Aug 2, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, MOOC MBA Design

I just finished another outstanding course, “Foundations of Business Strategy,” taught by Michael J. Lenox of the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia. Like Wharton, Darden is a leader in providing B-school content via MOOC. This course was dense with content. In just six weeks we covered:

- The concept of strategic analysis and the impact of competitive markets on business success

- How to analyze industry forces

- How to analyze firm capabilities

- How to analyze competitive dynamics

- How an organization can best position itself competitively to create value

- How to analyze firm scope

As you can tell from the number of times the words “how to” appear in the above list, this course was very focused on building practical skills. In addition to two or so hours of video lectures each week and readings from a book called The Strategist’s Toolkit, each week also included a case study from a particular industry – also with reading and analysis required. Additionally, a key requirement of the course was to conduct a strategic analysis of a real business and draft a report with hard data and specific strategic recommendations.

Six weeks. Normally, I like MOOCs that hold me to a schedule; the schedule keeps me focused and prevents the course from dragging on. However, while the content in this course was fantastic, my one complaint was that I didn’t really have time to engage with all of it. I normally spend about 4 hours per week on a course. This one could have easily used 10. In fact, I may take this course again next time it’s offered. That’s the beauty of MOOCs.

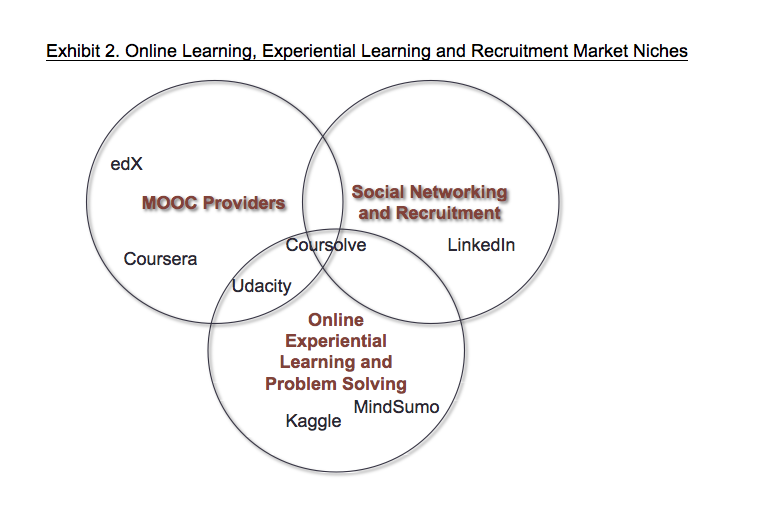

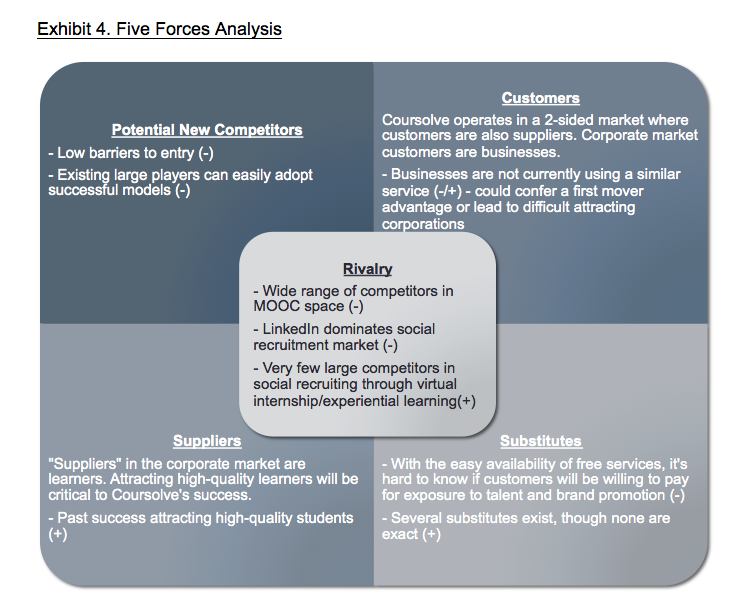

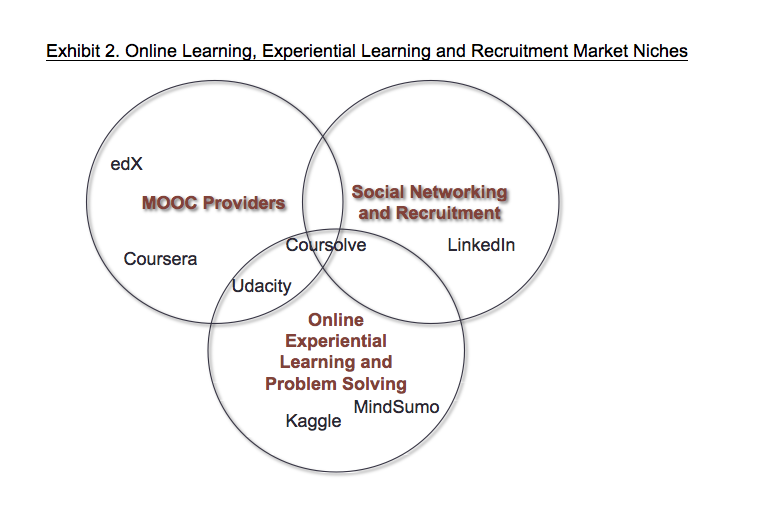

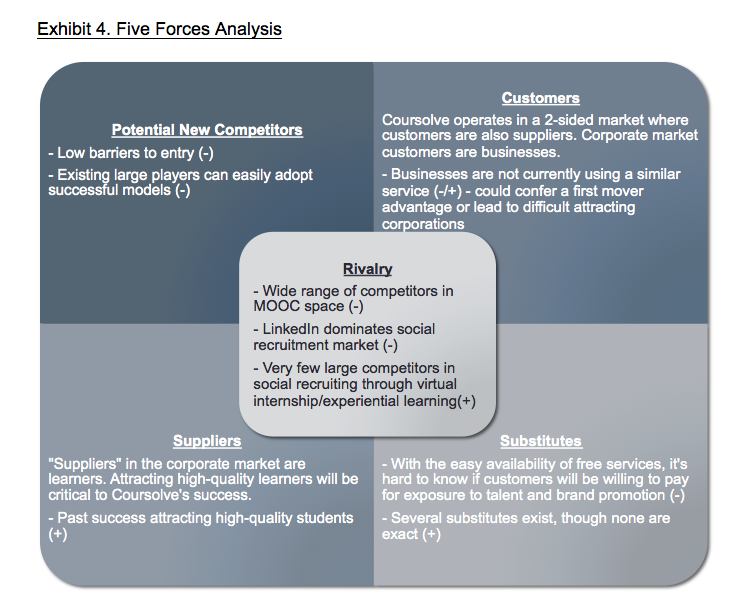

What I chose to focus on this time around was the final project. I registered for this course in part because I had recently heard about Coursolve, an online experiential learning platform that connects MOOC students with real companies. The companies post needs that correspond to the skills covered in the MOOCs, and students can try out their new skills solving real-world problems. Rather than basing my final project on a well-known company with which I had no personal connection, I was able to browse the needs posted on Coursolve and choose a real-world situation to work on.

If you’re taking business MOOCs and you haven’t heard of Coursolve before, I strongly encourage you to check out what they’re offering. The needs relevant to my business strategy course ranged from an HR company trying to figure out the needs of its customers, to a mining company looking to go public, to an Indian clean tech company trying to come up with a marketing plan. For my final project, I chose to work with Coursolve itself, as this online startup is still crafting its own business model.

Between the case studies and the final project, which will be assessed by my classmates, “Foundations of Business Strategy” offered above-average opportunities for interaction, skill-building, and experiential learning. Some people question the ability of online courses to teach a subject like strategy. This course proved to me that it can indeed be done, and quite well.