by Laurie Pickard | Jan 21, 2014 | Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

Since an article about the No-Pay MBA went viral on LinkedIn, I have received an overwhelming response to my project. The LinkedIn article was viewed over 350,000 times (and counting) and shared over ten thousand times. Over 700 comments were posted on it.

Since an article about the No-Pay MBA went viral on LinkedIn, I have received an overwhelming response to my project. The LinkedIn article was viewed over 350,000 times (and counting) and shared over ten thousand times. Over 700 comments were posted on it.

I want to say thank you to all those who have reached out to me. In the past week, I have received hundreds of contact requests on LinkedIn, dozens of comments on my blog, a slew of shout-outs on Twitter, and many new subscribers to the No-Pay MBA newsletter. While many of the comments on the LinkedIn article were skeptical, everyone who reached out to me directly was enthusiastic about the potential of this method of learning. Your support has been overwhelming and inspiring.

Unfortunately, in order to respond individually to everyone who contacted me, I would probably have to quit my job, so please don’t be offended if I don’t reply to you with a personal message. I’ve tried to be transparent about what I’m doing, so most of the questions I’ve been asked in personal messages are answered on the blog (e.g. What courses are you taking? How did you decide which courses to take? Are you getting credit towards a regular degree? Don’t you think you’re missing out on the MBA network?)

If you’ve read through the blog and still have questions, I encourage you to post them publicly as comments on the blog so that I can respond in a way that benefits other readers who might have similar questions. And please keep the feedback and suggestions coming! I also encourage you to chime in on any of the online discussions that are taking place around this concept. Even though not everyone is convinced that the No-Pay MBA is the wave of the future, I’m thrilled to have sparked such a lively discussion.

Finally, I’d like to share a few of my favorite comments and exchanges inspired by the article:

On the LinkedIn post:

“Depending on where she applies for her next job, I’m sure some employers will be impressed by her resourcefulness if she actually completes it - this is the stuff cover letters are made of. If her actual skills/knowledge is put in question, employers can do what they do with every other employee and administer some kind of test or pepper the interview with intentional questions about her knowledge.”

“True, she won’t be receiving any accredited degree but she will be showing that she completed the same course load as an accredited MBA which to me shows some ingenuity in the method of receiving the education. Isn’t this an example of what true forward thinking corporations want in an employee that thinks outside the box? Sure, not every firm is going to see this as an MBA equivalent or even a smart approach, but those are probably the firms that sort candidates based on where the candidate went to school without even evaluating the candidate’s potential, etc. This is also not the same as just reading some books. These are college level courses taught by tenured professors with testing in some cases. The only issue for a potential employer is of course verifying the validity of a MOOC MBA but I imagine at least for the foreseeable future there will not be a tremendous amount of them so to take a chance on a person won’t be a big deal. Plus, MBA level people already have an extensive work history at this point in their careers.”

On a related Poets and Quants article:

“Commenter1: This is awesome! Just curious, how would you list this on a resume? What ethical guidelines are there for listing yourself as an MBA from a MOOC?

“Commenter 2: Here’s how I see it: You would include a one-page overview of your MBA studies, listings the courses you’ve taken, the schools that sponsored them, the dates you completed them, and the grades you’ve received. You would divide the courses up by “core courses” and “elective courses.” And you would say you did what no mainstream MBA has ever done: Taken a full load of MBA courses on your own which demonstrated self-discipline, a thirst for learning, and the hard work to see it all through–and you are smart enough to get your MBA for free, saving yourself more than a quarter of a million dollars in tuition, school fees, and opportunity costs. What’s more, you will have gotten it by studying with professors from the world’s best business schools: Wharton, Yale, Stanford, Virginia, Northwestern, etc. You will even be able to say you took a course from a recent Nobel Prize winner, Robert Shiller of Yale, whose course on financial markets is coming out this February.

“Now this isn’t going to work at a McKinsey or Bain, but I think it would impress most employers greatly and make a difference in your employment prospects. And if you are able to pull this off you will have learned everything an MBA at Harvard or Chicago will have learned. You won’t have the network or the ideal sequence of learning that is part of a highly organized, lockstep MBA program. But it’s free!”

On my most recent blog post:

“Folks can debate till the end of time on how effective MOOCs can be w/o a stamp or piece of paper, but in the end, it’s the ones devoted to learning and building something useful out of it that will create the learning structure they need and come out with a story to tell on a resume or interview, and no one says networking is limited to B-school.

“Besides, by the time traditionalist MBA kids are done forking over $100k and polishing their resumes for jobs, you’ll be ready to apply what you’ve learned and start hiring them.

“Thanks for choosing to be so open to share your experiences; I’m on a similar path (science oriented), but am happily learning more now than I have in years. Onwards!”

by Laurie Pickard | Jan 17, 2014 | Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

It’s been an exciting few days, with an article about the No-Pay MBA appearing on Poets and Quants, CNN Money/Fortune, and a host of other websites. I couldn’t be happier about the press coverage. The overall response to my project – in comments on my website and on the articles, and through Facebook and social media shares – has been incredibly positive. I’ve even heard from a few people who have been inspired to start their own MOOC-based educational programs.

It’s been an exciting few days, with an article about the No-Pay MBA appearing on Poets and Quants, CNN Money/Fortune, and a host of other websites. I couldn’t be happier about the press coverage. The overall response to my project – in comments on my website and on the articles, and through Facebook and social media shares – has been incredibly positive. I’ve even heard from a few people who have been inspired to start their own MOOC-based educational programs.

I have also, however, received a few skeptical comments. Several people have asked whether a university will be granting me a degree at the end of all this. (Answer: No.) One even wondered what would be the point of doing all this work if I wasn’t expecting to get a degree out of it.

I’m happy to accept criticism of my project – in fact, it is only by addressing its weaknesses that I can improve it. So thank you to those who have raised these questions. While thinking about the issues readers have raised, I have also been considering the material I am learning in my course on how to build a startup. One of the core components of building a startup is defining its value proposition. It is critical to understand exactly what problem your product is trying to solve, and for whom. Although I don’t have any current plans to turn the No-Pay MBA into a business, I do care about providing a valuable product to my “customers,” i.e. my readers.

I assume that, like me, my customers would like to have an MBA, but aren’t convinced that traditional degree programs are worth the time and money they cost. I created the No-Pay MBA as a solution to that problem – but as my critics have recognized, so far it is only a partial solution. The value of any degree can be broken down into three parts: what you learn, signaling, and connections. Let’s consider how the No-Pay MBA might address each of these.

Skills and knowledge are the foundation

One of my biggest questions before starting this project was whether enough information was out there, freely available, to add up to an MBA, and whether I could absorb that material through the MOOC format. The more MOOCs I complete and the more courses that come online, the more I believe that there is plenty material out there, and that I can in fact absorb it. I won’t have a problem learning as much as or more than I did in my brick-and-mortar graduate program. Especially interesting for me in reading the responses to the Poets and Quants article is that almost no one has questioned my ability to learn B-school material through MOOCs.

Again, I am reminded of my course on startups. The instructor says over and over that the only way to test your hypotheses is to “get out of the building” and speak to your potential customers. When I first started this project, I thought that the primary value of my blog would be to provide readers with a roadmap for combining courses into an MBA so that they too could acquire business skills free of charge. I still do see the roadmap function as being an important part of the blog, but I can see that there are other “pains” (to use the language of the startups course) associated with getting a MOOC-based MBA that I could address.

A school is a brand

While new skills and information are the backbone of an education, they do not comprise its entire value – otherwise there’s no way top B-schools would be able to command upwards of $100,000 for a two-year degree when much of what they teach is available free of charge. Much of the value, and for some people the lion’s share of it, comes from the other two components – the signaling and the network.

What do I mean by signaling? When an employer sees on your resume that you got an MBA from Harvard Business School, he or she assumes you are top-notch. If you got into Harvard, you must be smart, and if you finished, you must have learned something. That is the signal that the Harvard name sends. In other words, a degree-granting institution functions like a brand.

A MOOC can’t provide the first part of the signal, since there isn’t any admissions process. It is, however, possible that some of the prestige of the universities offering MOOCs will rub off on the students who complete them – I certainly hope that is the case. But it remains to be seen whether employers will read completion of a series of MOOCs from prestigious schools as a signal of actual learning.

As I’ve said, I know I’m learning. So how can I bring credibility to the No-Pay MBA? Appearing on CNN Money certainly helps my individual case, but will it help anyone besides me? I do think that a highly publicized example can help other people by raising awareness about the possibilities MOOCs present.

I wonder whether MOOC students would find value in third-party verification – not a stack of Statements of Accomplishment, but a certificate from another provider that attests to your completion of a course of study. For a model of this approach, check out Skills Academy.

The value of a network

Most of the comments I received questioning the value of the No Pay MBA centered on signaling, but I also see a great opportunity for networking among “graduates” of self-designed degree programs. If we can organize ourselves, we could help each other out by sharing information, offering advice, and making real-world connections. I would love to see the No Pay MBA site become a hub for people pursuing MOOC-based MBAs.

If you are attempting a MOOC MBA and can think of other ways this website can help you out, I would love to hear from you.

by Laurie Pickard | Jan 3, 2014 | Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

One of the best things about a No-Pay MBA is that you can start one any time. Because new MOOCs are starting pretty much continuously, it isn’t necessary to stick to a semester schedule. Still, it can be helpful to break up the year into chunks, and many new classes are released around when college semesters typically start. So, as we head into spring semester, here are a few tips to help as you choose your courses.

One of the best things about a No-Pay MBA is that you can start one any time. Because new MOOCs are starting pretty much continuously, it isn’t necessary to stick to a semester schedule. Still, it can be helpful to break up the year into chunks, and many new classes are released around when college semesters typically start. So, as we head into spring semester, here are a few tips to help as you choose your courses.

1. Go in with an idea of the topics you’d like to study, but be flexible.

I think it’s a good idea to have an overarching structure to guide you, rather than just taking business courses willy nilly. That said, because it’s hard to predict which courses will be available when, it’s important to remain flexible. For example, I had planned to take a marketing course this semester, but I haven’t found any yet. So instead I’ve chosen to take some advanced courses in finance and entrepreneurship, which I was planning to do the following semester.

2. Choose courses from a variety of sites.

When it comes to business and management courses, Coursera has the best selection by far. But don’t forget about NovoEd, Open2Study, Udacity, and Canvas, all of which have a good selection of business courses as well. Not all of my courses are taught by university professors either. I am working on a Udacity course on entrepreneurship with a teacher who is a phenomenal lecturer with loads of real-world business experience. For my purposes, it doesn’t matter that he isn’t connected with a university.

3. Set up a mail filter.

I highly recommend sending all of your MOOC-related mail to a dedicated folder. If you use Gmail – and who doesn’t these days? – and don’t know how to set up a filter, you can learn how to do it here. As soon as I register for a new MOOC site, I immediately set up a filter to send all mail from that site’s domain name to go to my “MBA” folder. That way, there’s only one place in my inbox to look for all course updates.

4. Do a trial or “shopping” period, then un-register from courses you don’t want to take.

When I was in college, at the beginning of every semester I would register for a dozen classes, attend each of them a couple of times, and then make a final decision about which of them to attend for the entire semester. I recommend a similar strategy for your No-Pay MBA coursework. So far, I am registered for a course in human resources, one on financial markets, one on entrepreneurship, one on financial analysis of entrepreneurial ideas, and one from the HEC School of Management in Paris (in French, I might add) on valuation. If my schedule looks a bit finance-heavy, well it is. I don’t plan to finish all of these courses – I just want to test them out. If you “shop” a bunch of couses before you commit, I think it’s polite to un-register once you’ve decided which ones you’re not interested in finishing. It also cuts down on email clutter.

5. Leave a little room in your schedule for surprises.

Last semester my schedule was so packed I didn’t have time to add any new courses mid-way through. But what if Harvard Business School finally releases it’s long-awaited MOOC series? I want to have some time in my schedule to take a really good course that pops up.

by Laurie Pickard | Dec 20, 2013 | MOOC MBA Design, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

By far the biggest challenge when taking an online course is maintaining motivation. With no professor to praise you, no fellow students to foster competition, and – in a MOOC, at least – no credit-granting institution to hold you accountable, you have only your own will power and determination to get you through. Finishing one course – let alone enough courses to add up to a degree - requires a disciplined, intrinsically motivated student.

The numbers tell a similar story. The New York Times recently reported on a University of Pennsylvania study on MOOCs whose headline stats included the fact that fewer than 4% of students finish the courses they register for, and 80% of those enrolled in MOOCs already hold a university degree. These results prompted Forbes to ask if MOOCs are in fact failing in their mission of democratizing education.

To my mind, it’s much too early to label MOOCs a failure. The fact that so many people are interested enough to register for these courses – regardless of whether they finish them – indicates the vast potential of MOOCs. Besides, there are plenty of good reasons why a person might sign up for a course and not finish it. Maybe they were simply curious about the whole MOOC phenomenon and never intended to take a whole course. Maybe they understimated the amount of work involved. Maybe they started the course and then decided the assignments weren’t worth their time. (I’ll be honest, I’ve definitely shirked some assignments in my current MOOC. Don’t even get me started on how much I hate it when 120,000 students are given the assignment of posting a comment on a class-wide discussion forum.)

It all boils down to motivation.

So what might make it easier to sustain the motivation required to finish an online course? Anything that makes the student more socially accountable. Nobody wants to be seen as a slacker or a quitter, but as an anonymous student in an online class it hardly matters if you complete your assignments or not.

My personal solution to the motivation problem is to blog about my courses. Because I’ve made a personal commitment to write about my MBA experience in a public forum, I’m motivated to complete my courses – both to have new material to write about and to make good on what I’ve set out to accomplish.

But any strategy that fosters social accountability could have a similar effect. For example, telling friends and family that you plan to take a course can make it more likely that you’ll finish it. Discussion forums with thousands of students are useless, but a study group – even a virtual one – with just a few students could provide the necessary social accountability. Even better would be a live discussion section with a mentor or facilitator.

For me, the most difficult assignments are those that involve writing or creating something. Problem sets and multiple choice quizzes are easy by comparison. So I’m telling you now, I plan to work harder on creative assignments next semester. You can hold me to that.

by Laurie Pickard | Dec 8, 2013 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

A recent Huffington Post blog entry asks the question, how do you define a MOOC? For example, how big does a course have to be to be considered “massive”? Does a course have to be completely free to be considered “open”? And what exactly is a “course” anyway? For example, does a podcasted lecture count as a course?

I am not overly concerned about whether my coursework falls into the MOOC genre. Rather, what matters to me is that my courses be free or nearly free, that they cover subjects that are MBA-relevant, and that they allow me the opportunity achieve mastery in a subject area.

I’ve taken several different types of free courses since I started this project. My first was a class on coffee price risk management offered by the World Bank. It wasn’t technically a MOOC because it wasn’t open – I needed a CD with an access code to take it – but it was similar to a MOOC in that I was responsible for supplying the motivation to get through the course, and there was no teacher to help me out if I got stuck. I’ve since taken courses on iTunesU, Coursera, Canvas Network, and Open Yale.

Based on that diversity of coursework, here are my criteria for what makes a good MOOC. (Bear in mind that I’m using the term “MOOC” loosely.)

- The course should be intended for an online audience.

It has been much easier for me to learn in courses that are actually intended for an audience that is not physically in the same room as the teacher. While it’s cool to be able to listen in on the regular live classes of top professors, it’s difficult to truly follow along when you’re missing so much of the face-to-face interaction of the classroom. This turns out not to be a problem in a course where the professor is speaking to online students.

2. A course that follows a defined schedule is better than a self-paced course.

I’ve taken courses with a set schedule and deadlines for homework assignments and exams. These courses are much easier to finish than those that require the student to pace themselves for the whole course. That said, flexibility is also a virtue. It’s best when the course offers a window of about two weeks to complete an assignment. That way a heavy week at work won’t totally throw you off track.

3. A simple layout is best.

I’ve taken most of my courses so far on Coursera, primarily because the offerings are so much better than any competitor’s. But now that I’ve started a course on a another site – Canvas Network – I must say I have a strong preference for Coursera’s layout. The side bar on the course home page shows me everything I want to see – links to video lectures, homework assignments, the course syllabus, and the discussion forum all in one place. Canvas walks you through the course, from one module to the next, with the quizzes and discussion forums threaded through. Unfortunately, this system makes it much more complicated to find anything. I recently discovered a series of homework assignments I had missed because I hadn’t correctly navigated the course modules.

4. Multiple forms of information delivery can be effective.

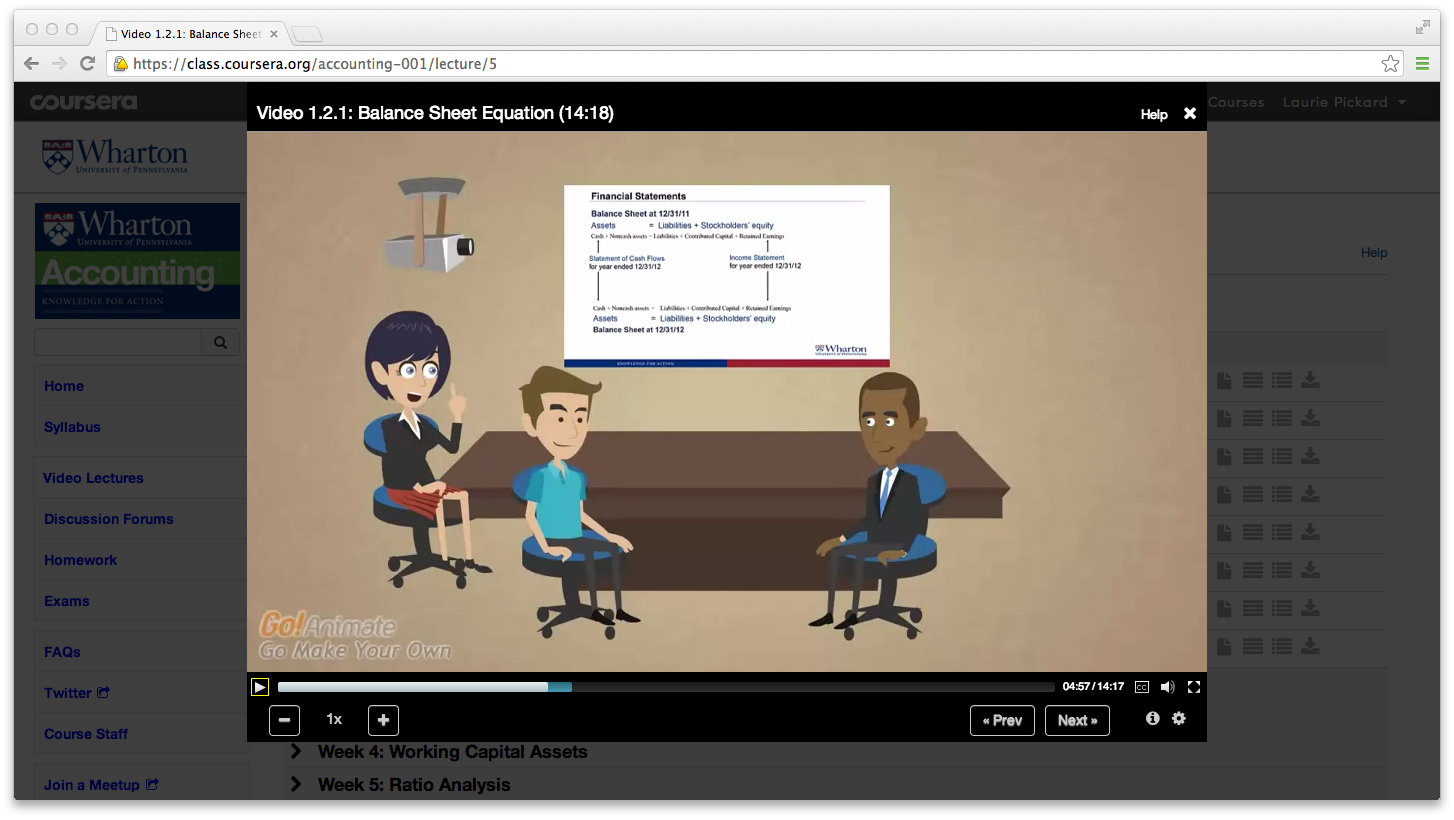

Coursera courses are based around video lectures, often with Power Point slide shows worked through. Canvas uses more text pages, with some live (and later archived) video discussions. The World Bank coffee course I took was almost all text. Some courses have included links to external sites – whether to provide supplemental information, real-world examples, or practice with concepts. All of these forms of delivering information are effective. My Accounting teacher went above and beyond by including animated virtual students in his video lectures, but that’s really not necessary.

5. Don’t just give an overview; go into detail.

I don’t know if it’s that they didn’t have the time to do a thorough job or if they think online students won’t get it, but some of my courses have been too superficial. The main culprits here are International Organizations Management and, as I’m coming to find out, Project Management Skills for All Careers. It really irks me when the professors allude to a skill set that is necessary in the subject they are teaching, then gloss over the technicalities of employing that skill set. For example, my Project Management class recently had a module explaining the importance of making the business case for a new project, but didn’t go into any specifics about how to do the analysis, or how to present the results!

6. Make the homework difficult.

My biggest pet peeve is when instructors assign posting to the discussion forum as homework. The forum gets so crowded with useless posts. “I agree with what So-and-so said.” Or, “Thank you, professor, for an interesting lecture.” You scroll through hundreds of these comments, only to post your own superfluous message and get “credit” for it. Another pet peeve is easy quizzes. If I can ace the quiz without listening to the lecture, it needs to be more difficult. Problem sets are the best kind of homework. Preferably difficult ones. Kudos to my professors of Accounting and Operations Management for making good problem sets and hard quizzes.

In summary, a good MOOC is one that is simple to navigate, that works within the limitations of an online platform, and that is challenging enough to be rewarding.

In other words, give me what I need to succeed, then make me work for it.

My Accounting course is a great example in this regard. Sure, it was difficult, but in the end almost 10,000 of us will be receiving a Statement of Accomplishment. And for this course, I’m truly proud to have earned it.

by Laurie Pickard | Oct 31, 2013 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

My most disappointing course this semester was International Organizations Management. I chose the course because I work in this field and was curious what the instructors would present. The course was taught by a group of professors from the University of Geneva, all of whom are on the faculty of that university’s international MBA program. As I’ve mentioned previously, most of the jobs in international development, and I would imagine in international organizations more generally, are management jobs. However, our training is mostly theoretical, so one must learn the practical skills of management while on the job. I was hoping that this class would cover some of these skills, especially since the recommended background for the course was “Graduate students of international relations/business management/international law and/or professionals with a few years of relevant work experience.”

I was sorely disappointed – yet another class longer on theory than practice.

I was hoping for best practices related to the work that I do, for example:

- Managing a project budget

- Conducting and participating in meetings

- Creating a work plan and project timeline

- Crafting a monitoring and evaluation plan, including setting targets and choosing indicators

- How to design a public private partnership (the course did touch on this, but didn’t get into specifics)

Alas, what I got instead was more an overview and history of the UN system than any practical tools for operating in the international arena (in which, incidentally, the UN is only one player, and not necessarily the most important player at that!).

Interestingly, the one module of the course that I really enjoyed was the one on marketing, not a topic in which I had any prior interest. What I liked about the module was that it spoke about particular techniques for making a marketing plan, including specific questions that an organization needs to answer in order to make a strong plan. The course also made me realize that I have had the wrong understanding of marketing, probably because most international organizations approach marketing as though it were of secondary importance – an afterthought.

The following graphic shows the place of marketing in most international organizations.

Marketing falls below communications, which itself is a third-tier category. Contrast that with the position of marketing in the private sector.

In a private sector company, marketing is directly under the CEO and is responsible not just for PR and promotion but is integrally involved with crafting the overall strategy for the company and in building its identity.

Even though I didn’t learn much in International Organizations Management that I can apply on the job, I did benefit from the course in that it piqued my interest in marketing - one of the topics for next semester. So in the end, I’m glad I stuck it out.

Since an article about the No-Pay MBA went viral on LinkedIn, I have received an overwhelming response to my project. The LinkedIn article was viewed over 350,000 times (and counting) and shared over ten thousand times. Over 700 comments were posted on it.

Since an article about the No-Pay MBA went viral on LinkedIn, I have received an overwhelming response to my project. The LinkedIn article was viewed over 350,000 times (and counting) and shared over ten thousand times. Over 700 comments were posted on it.

One of the best things about a No-Pay MBA is that you can start one any time. Because new MOOCs are starting pretty much continuously, it isn’t necessary to stick to a semester schedule. Still, it can be helpful to break up the year into chunks, and many new classes are released around when college semesters typically start. So, as we head into spring semester, here are a few tips to help as you choose your courses.

One of the best things about a No-Pay MBA is that you can start one any time. Because new MOOCs are starting pretty much continuously, it isn’t necessary to stick to a semester schedule. Still, it can be helpful to break up the year into chunks, and many new classes are released around when college semesters typically start. So, as we head into spring semester, here are a few tips to help as you choose your courses.